Corona virus and blood types

The novel coronavirus causing COVID-19 seems to hit some people harder than others, with some people experiencing only mild symptoms and others being hospitalized and requiring ventilation. Though scientists at first thought age was the dominant factor, with young people avoiding the worst outcomes, new research has revealed a suite of features impacting disease severity. These influences could explain why some perfectly healthy 20-year-old with the disease is in dire straits, while an older 70-year-old dodges the need for critical interventions.

Underlying health conditions are thought to be an important factor influencing disease severity. Indeed, a study of more than 1.3 million COVID-19 cases in the United States, published June 15 in the journal Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, found that rates of hospitalizations were six times higher and rates of death were 12 times higher among COVID-19 patients with underlying conditions, compared with patients without underlying conditions. The most commonly reported underlying conditions were heart disease, diabetes and chronic lung disease.

The novel Coronavirus disease (COVID-19, caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus) has spread rapidly across the globe and has caused over 21.1 million confirmed infections and over 761,000 deaths worldwide as of August 17, 2020.

A number of risk factors for COVID-19 morbidity and mortality are known, including age, sex, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and chronic cardiovascular and respiratory diseases .

Recent work has demonstrated an association between ABO blood types and COVID-19 risk.

The rapid global spread SARS-CoV-2 has strained healthcare and testing resources, making the identification and prioritization of individuals most at-risk a critical challenge. Recent evidence suggests blood type may affect risk of severe COVID-19.

The ABO blood type trait reflects polymorphisms within the ABO gene. This gene is associated with a number of other traits, including risk factors for COVID-19 morbidity and mortality. For example, genome-wide association studies have associated variants within ABO to activity of the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), red blood cell count, hemoglobin concentration, hematocrit,von Willebrand factor, myocardial infarction ,coronary artery disease, ischemic stroke , type 2 diabetes , and venous thromboembolism .

The ABO blood type trait reflects polymorphisms within the ABO gene. This gene is associated with a number of other traits, including risk factors for COVID-19 morbidity and mortality. For example, genome-wide association studies have associated variants within ABO to activity of the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), red blood cell count, hemoglobin concentration, hematocrit,von Willebrand factor, myocardial infarction ,coronary artery disease, ischemic stroke , type 2 diabetes , and venous thromboembolism .

A 2012 meta-analysis found that, inaddition to individual variants, a non-O blood type is among the most important genetic risk factors for venous thromboembolism. These conditions are also relevant for COVID-19. For example, coagulopathy is a common issue for COVID-19 patients , and risk of venous thromboembolism must be carefully managed .

The numerous associations between conditions and both blood type and COVID-19 provide reason to believe true associations may exist between blood type and morbidity and mortality due to COVID-19. In addition, previous work has identified associations between ABO blood groups and a number of different infections or disease severity following infections, including SARS-CoV-1 , P. falciparum , H. pylori , Norwalk virus , hepatitis B virus ,and N.

Blood type seems to be a predictor of how susceptible a person is to contracting SARS-CoV-2, though scientists haven’t found a link between blood type per se and severity of disease.

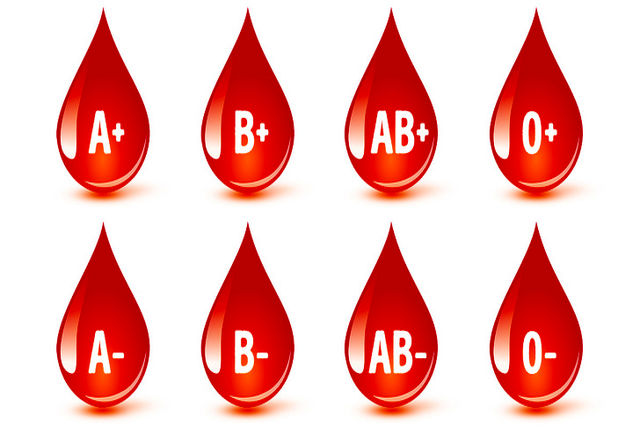

Jiao Zhao, of The Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, and colleagues looked at blood types of 2,173 patients with COVID-19 in three hospitals in Wuhan, China, as well as blood types of more than 23,000 non-COVID-19 individuals in Wuhan and Shenzhen. They found that individuals with blood types in the A group (A-positive, A-negative and AB-positive, AB-negative) were at a higher risk of contracting the disease compared with non-A-group types. People with O blood types (O-negative and O-positive) had a lower risk of getting the infection compared with non-O blood types, the scientists wrote in the preprint database medRxiv on March 27; the study has yet to be reviewed by peers in the field.

Jiao Zhao, of The Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, and colleagues looked at blood types of 2,173 patients with COVID-19 in three hospitals in Wuhan, China, as well as blood types of more than 23,000 non-COVID-19 individuals in Wuhan and Shenzhen. They found that individuals with blood types in the A group (A-positive, A-negative and AB-positive, AB-negative) were at a higher risk of contracting the disease compared with non-A-group types. People with O blood types (O-negative and O-positive) had a lower risk of getting the infection compared with non-O blood types, the scientists wrote in the preprint database medRxiv on March 27; the study has yet to be reviewed by peers in the field.

In a more recent study of blood type and COVID-19, published online April 11 to medRxiv, scientists looked at 1,559 people tested for SARS-CoV-2 at New York Presbyterian hospital; of those, 682 tested positive. Individuals with A blood types (A-positive and A-negative) were 33% more likely to test positive than other blood types and both O-negative and O-positive blood types were less likely to test positive than other blood groups. (There’s a 95% chance that the increase in risk ranges from 7% to 67% more likely.) Though only 68 individuals with an AB blood type were included, the results showed this group was also less likely than others to test positive for COVID-19.

The researchers considered associations between blood type and risk factors for COVID-19, including age, sex, whether a person was overweight, other underlying health conditions such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, pulmonary diseases and cardiovascular diseases. Some of these factors are linked to blood type, they found, with a link between diabetes and B and A-negative blood types, between overweight status and O-positive blood groups, for instance, among others. When they accounted for these links, the researchers still found an association between blood type and COVID-19 susceptibility. When the researchers pooled their data with the research by Zhao and colleagues out of China, they found similar results as well as a significant drop in positive COVID-19 cases among blood type B individuals.

Why blood type might increase or decrease a person’s risk of getting SARS-CoV-2 is not known. A person’s blood type indicates what kind of certain antigens cover the surfaces of their blood cells; These antigens produce certain antibodies to help fight off a pathogen. Past research has suggested that at least in the SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV), anti-A antibodies helped to inhibit the virus; that could be the same mechanism with SARS-CoV-2, helping blood group O individuals to keep out the virus, according to Zhao’s team.

Prepared:

Neshat Khosravi – Microbiologist

Reference:

https://www.livescience.com

Recent Comments