Brain damage and coronavirus

More than Six months into the COVID-19 pandemic, we’re still learning what the disease can do. There are now detailed reports of brain illness emerging in people with relatively mild lung illness, in those who are critically ill and also in those in recovery.

One key thing we’re seeing is that severity of lung illness doesn’t always correlate with severity of neurological illness. Having only minor lung illness doesn’t protect against potentially severe complications.

As the number of COVID-19 patient records grows, researchers are meticulously combing through the data, searching for a better understanding of the virus and what we can expect in the months and years ahead. What is now of increasing concern in health care is the realization that the virus can not only be severe, but can also have long-term consequences.

Respiratory and skeletal muscle consequences surfaced earlier in the pandemic. More recently, the neurological and neurocognitive aspects of the virus have become a major concern. The neurocognitive symptoms linked to coronaviruses, counting COVID-19, include delirium, both acute and chronic attention and memory deficits linked to hippocampal and cortical damage, as well as learning deficits in both adults and children.

These symptoms feature significantly in a large percentage of COVID-19 patients. In March, a study reported 36.4 per cent of COVID-19 patients have neurological symptoms, including headache, disturbed consciousness and paresthesia (a burning or prickling sensation in parts of the body such as hands, legs and feet). Not surprisingly, severely affected patients are more likely to develop neurological symptoms than patients who have mild or moderate disease.

a report published in early June that 84 per cent of the patient sample had neurologic symptoms. Also, using autopsy reports on patients who had severe cases noted brain tissue edema (a life-threatening condition that causes fluid to develop in the brain, causing pressure inside the skull) and neuronal degeneration (when a brain’s neurons break down, lose connectivity and affect brain function).

Assessing neurological symptoms

The percentage of COVID-19 patients with neurological symptoms varies greatly between studies. One of the reasons is inconsistent assessment methods. Research has shown behavioural assessment (testing based on things like the patient’s visual responses, motor function and communication) is frequently inaccurate.

Reliable neurocognitive assessment procedures will be essential both in accurately assessing active and post-COVID patients’ cognitive abilities, and in tracking their recovery. Objective assessments of brain function can help pinpoint when neurocognitive symptoms begin to appear in COVID-19 patients, which patient groups are at a higher risk, how long neurological effects may last and what treatments are most effective. In the early stages of understanding COVID-19 and researching the neurological effects, definitive facts around these issues remain unknown.

When it comes to the brain and nerves, the virus appears to have four main sets of effects:

-A confused state (known as delirium or encephalopathy), sometimes with psychosis and memory disturbance.

-Inflammation of the brain (known as encephalitis). This includes a form showing inflammatory lesions – acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) – together with the effects of low oxygen in the brain.

-Blood clots, leading to stroke (including in younger patients).

-Potential damage to the nerves in the body, causing pain and numbness (for example in the form of post-infectious Guillain-Barré syndrome, in which your body’s immune system attacks your nerves).

To date, the patterns of these effects seem similar across the world. Some of these illnesses are fatal and, for those who survive, many will bear long-term consequences.

This raises an important question: will COVID-19 be associated with a large epidemic of brain illness, in the same manner that the 1918 influenza pandemic was linked (admittedly somewhat uncertainly) to the epidemic of encephalitis lethargica (sleeping sickness) that took hold until the 1930s At this stage, it’s hard to say – but here’s what we know about the virus’s effects on the brain so far.

What’s happening inside people’s heads?

Firstly, some people with COVID-19 experience confused thoughts and disorientation. Thankfully, in many cases it’s short-lived. But we still don’t know the long-term effects of delirium caused by COVID-19 and whether long-term memory problems or even dementia in some people could arise. Delirium has been mostly studied in the elderly and, in this group, it’s associated with accelerated cognitive decline beyond what’s expected if patients already suffer dementia.

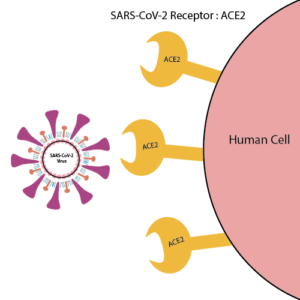

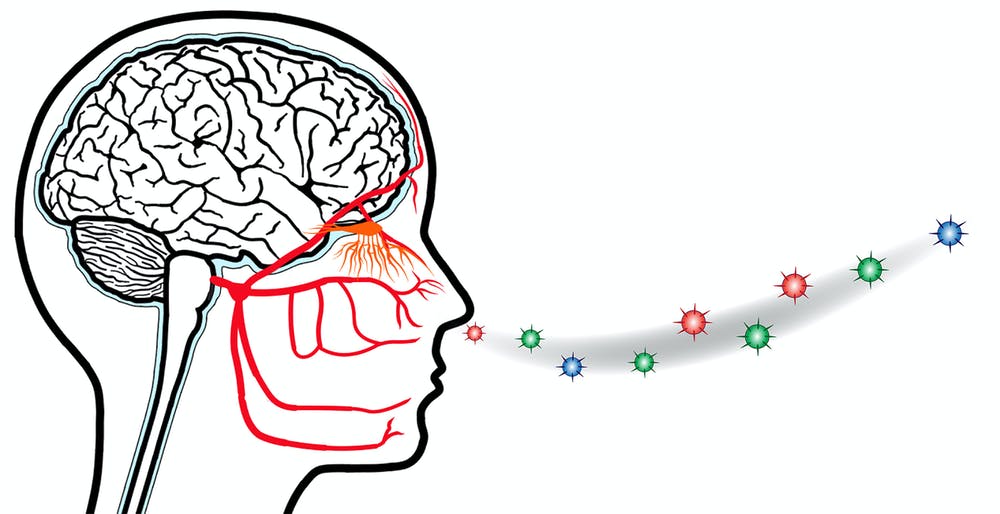

The virus also has the potential to infect the brain directly. However, most of the physical effects we’ve seen in survivors look like secondary impacts of the virus being present in the brain rather than the effects of direct infection. For example, our immune system can appropriately fight the virus, but may start to attack our own cells – including our brain cells and nerves. This may be through the actions of immune cells and antibodies via an inflammatory mechanism known as a cytokine storm, or through mechanisms we don’t yet understand.

There are also COVID-19 patients having ischaemic strokes, where a blood clot blocks the flow of blood and oxygen to the brain. Some of these patients have stroke risk factors (for example high blood pressure, diabetes or obesity), though their strokes have been particularly severe. It seems that this is because the blood rapidly becomes thickened in COVID-19 and, in these patients, there have been multiple blood clots in the arteries feeding blood to the brain, even in patients already receiving blood thinners. In others, there is brain bleeding due to weakened blood vessels, perhaps inflamed by the effects of the virus.

Where infection with the coronavirus is associated with inflammation or damage to the nerve endings themselves, individuals may develop burning and numbness and also weakness and paralysis. Often it’s difficult to know if these are the effects of a critical illness on the nerves themselves or if there’s brain and spine involvement.

All of these effects on the brain and nervous system have the potential for long-term damage and can stack up in an individual. But we need to know more about what’s going on in people’s nervous systems before we can accurately predict any long-term effects.

One way of finding out more is to take a look inside patients’ heads using brain-imaging techniques, such as MRI. So far, brain imaging has revealed a pattern of previously unseen findings, but its still very early days for using it in this pandemic.

patterns found included signs of inflammation and a shower of small spots of bleeding, often in the deepest parts of the brain. Some of these findings are similar to those seen in divers or in altitude sickness. They might represent the profound lack of oxygen being delivered to the brain in some patients with COVID-19 – but we are only starting to understand the full scope of the brain’s involvement in the disease. Brain-imaging and postmortem studies for those killed by COVID-19 have been limited to date.

prepare:

neshat khosravi- microbiologist

refrence:

Recent Comments